Danse Macabre, literally the “dance of death”, has long permeated popular culture. The ritual, which consists of dead humans or death personified dancing with the living, is widely found in literature, painting, music and film. It is, fundamentally, a form of momento mori (like these “Vanitas” paintings I have already written about) – a reminder of mortality and a declaration of the fragility and transient nature of all life and goods. Frequently, in danse macabre, the earth opens to eject the departed or death itself appears in a ghostly or skeletal form and establishes its all-consuming universality by mingling with young and old, male and female individuals from every rank and station of the society. The whole phenomenon is a comic, consolatory, even joyful, appropriation of and response to loss and grief.

One recent example can be located in the award-winning Graveyard Book (2008) by English writer Neil Gaiman. A type of Jungle Book set in a cemetery, The Graveyard Book is the story of Nobody “Bod” Owens, a kid whose family has been murdered. He is raised by ghosts. An excerpt:

Something was going on, Bod was certain of it. It was there in the crisp winter air, in the stars, in the wind, in the darkness. It was there in the rhythms of the long nights and the fleeting days. Mistress Owens pushed him out of the Owenses’ little tomb. “Get along with you,” she said. “I’ve got business to attend to.” Bod looked at his mother. “But it’s cold out there,” he said. “I should hope so,” she said, “it being winter. That’s as it should be. Now,” she said, more to herself than to Bod, “shoes. And look at this dress—it needs hemming. And cobwebs—there are cobwebs all over, for heaven’s sakes. You get along,” this to Bod once more. “I’ve plenty to be getting on with, and I don’t need you underfoot.” And then she sang to herself, a little couplet Bod had never heard before. “Rich man, poor man, come away. Come to dance the Macabray.”

The French composer Camille Saint-Saëns (1835-1921) wrote an unforgettable version, the tunes of which match the wicked humour of his Carnival of the Animals. Here is a performance of Camille Saint-Saëns’s Danse Macabre in Poland.

Walt Disney directed a short animated subject in 1929 called The Skeleton Dance:

Then, which film buff can miss the Swedish film The Seventh Seal (1957) by Ingmar Bergman, one of the finest events to have graced the screens. It is possibly the most magnificent portrayal of both the game of chess and death personified – as the Grim Reaper. Deriving its title from the Book of Revelation in the New Testament (8:1) and set during the Black Death, The Seventh Seal is the story of an epic chess match between Antonius Block, a medieval knight exhausted and disillusioned after fighting in the Crusades – and Death – a pale, enigmatic, monk-like, black-cowled figure. The film deserves a whole blog post – I will write it someday. Here, I will just mention the end scene, in which the character of Jof the juggler witnesses a solemn dance of death over the hills. He tells his wife:

I see them, Mia! I see them! Over there against the dark, stormy sky. They are all there. The smith and Lisa and the knight and Raval and Jons and Skat. And Death, the severe master, invites them to dance. He tells them to hold each other’s hands and then they must tread the dance in a long row. And first goes the master with his scythe and hourglass, but Skat dangles at the end with his lyre. They dance away from the dawn and it’s a solemn dance towards the dark lands, while the rain washes their faces and cleans the salt of the tears from their cheeks.

The scene:

Herein we find a setting not far removed from the origins of the phenomenon.

—-

In his 2013 book Imago Mortis: Mediating Images of Death in Late Medieval Culture, Ashby Kinch, a professor at the university of Montana, clearly explains the beginnings of Danse Macabre. I’d like to share an informative paragraph here:

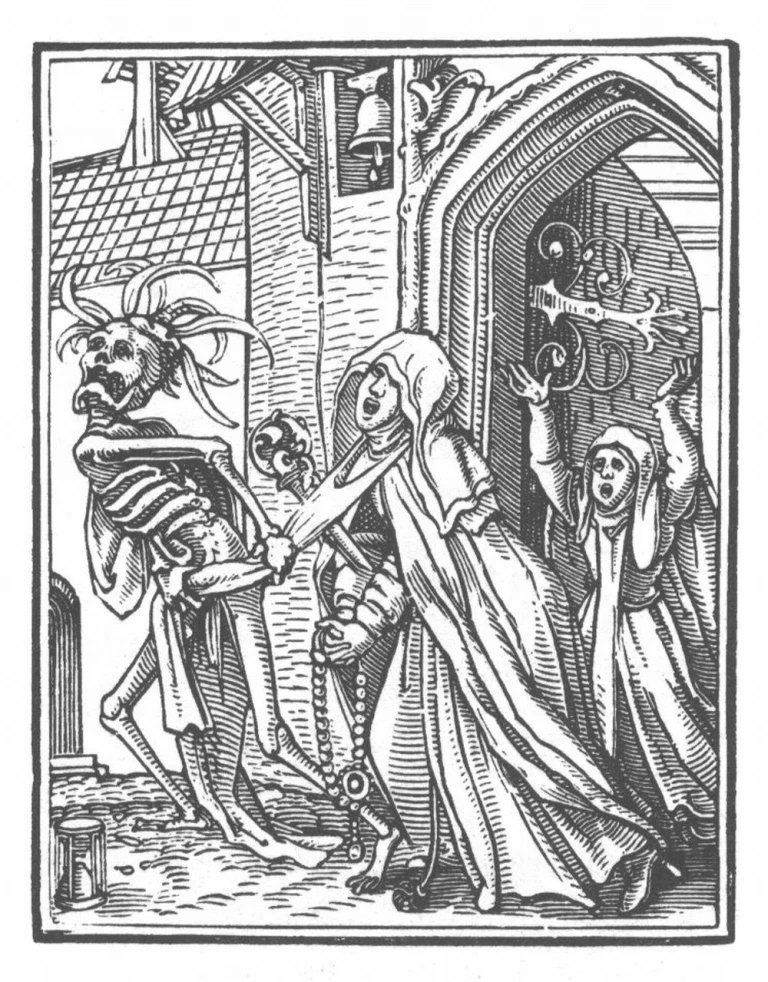

Between August 1424 and Lent 1425, an unknown artist, likely responding to a now-obscure theatrical tradition, painted the first known Danse Macabre mural on the outer wall of the Cemetery of the Innocents, facing the Rue de la Ferronerie, at the thriving heart of medieval Paris. Though now lost (the Cemetery was destroyed in 1786), the painting depicted decaying corpses dancing amidst typological representations of late Medieval society: a Pope, an Emperor, a Bishop, a King, a Monk, a Minstrel, and many more, 30 figures in all, ambling diffidently while the corpses frolic and mock them with jeering expressions, piercing remarks and aping grotesque movements of their bodies, beautifully baroque and accentuated by shark contrasts of flesh and painted costume. The form stunningly reverses the valence of the communities of the living and the dead: the dead rejoice in an active life – playing musical instruments, dancing, making conversation – while the living grow stiff, as their bodies rigidify and they lose their corporal identity. The alternation between dead and living creatures creates a rhythm of animation and stillness, of white and colour, a visual rhythm evocative of human culture itself. A new sense of community is achieved in and through the form, as the living face up to the dead, through whom they come to know concretely the abstraction of death. The social body is depicted in many of the murals as fluid and continuous, bound together by a common destiny that is re-enforced by the imagery of dance.

Take a look at the artwork:

Close-up:

And here is something funny and fascinating – not exactly Dance but the Triumph of Death.

—-

Further Reading:

Mixed Metaphors: The Danse Macabre in Medieval and Early Modern Europe edited by Sophie Oosterwijk and Stefanie Knöll (2011, Cambridge Scholars Publishing)

—-

![]()

This is great – I love dance macabre in art. There are some wonderful dance macabre music pieces too.

There is a traditional Columbian one I know of – which is a bit like Prokofiev’s Romeo & Juliet bit where Juliet is in a trance. I don’t know if you have heard of the British Midsomer Murders TV series but the theme tune to that is a very comedic Dance Macabre.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for that – I will check the series out!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I just viewed Disney’s “The Skeleton Dance” today–had forgotten about it. Makes more sense now than as a child as it is now linked for me with the many references you have cited.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Rare and mystifying imagery!

LikeLiked by 1 person

fascinating again ! I guess the mediaeval plague epidemics greatly increased their focus on death.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Certainly!! There’s a lot written on it – but I didn’t mention here for it would have got too long.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for a wonderfully intriguing piece. St Saen’s la Dance Macabre is one of my all time favorite pieces 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Michele! 🙂 Truly, St Saen’s work is spectacular. Hope you continue to enjoy the posts.

LikeLike

Love this piece. Superb topic! It’s got me feeling all warm and Halloweeny. I remember learning to play this on the cello when I was at school. Same time it was the theme tune for Johnathan Creek! Haunting and Nostalgic.

LikeLike

Thanks for commenting! Truly that piece is so amazing. Haunting, wicked and very exhilarating!

LikeLike

Enjoyed the Disney Skeleton Dance. “Memento mori” is a theme I think the post-modern world might benefit from revisiting. My favourite cathedral in the UK was Winchester – where they have graves of ancient bishops surmounted by skeletal effigies, reminding passers-by that we’ll all end up like that one day. These days it seems to be fashionable to want to live forever. What does that say about our sophisticated psychology?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I find the post-modern world’s relationship to life and death very weird. The irony is that – “Danse Macabre”, this very immersive contemplation of death, emerged out of a cultural context that believed in Resurrection, some possibility of an ultimate material regeneration. Whereas today people want to live forever themselves in the middle of a cultural context that considers entropy as the final word. Strange!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Possibly religion has its positive aspects 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

Much enjoyed your post and your collection of sources. I have been a fan of “Gothic” representations in culture for quite a long time. Totally agree with Alan above, the post-modern world has pretty much eliminated (or de-constructed out) any realistic confrontation with death in popular thinking. Ghastly slasher movies might be the exception (and they often end with a tension breaking resolution).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! 🙂 Hahah… ghastly slasher movies! We truly need more “graceful” engagements with the idea of death. The Gothic imagination pulled it off with unparalleled class.

LikeLike

Fascinating information!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! 🙂 Glad you enjoyed it!

LikeLike