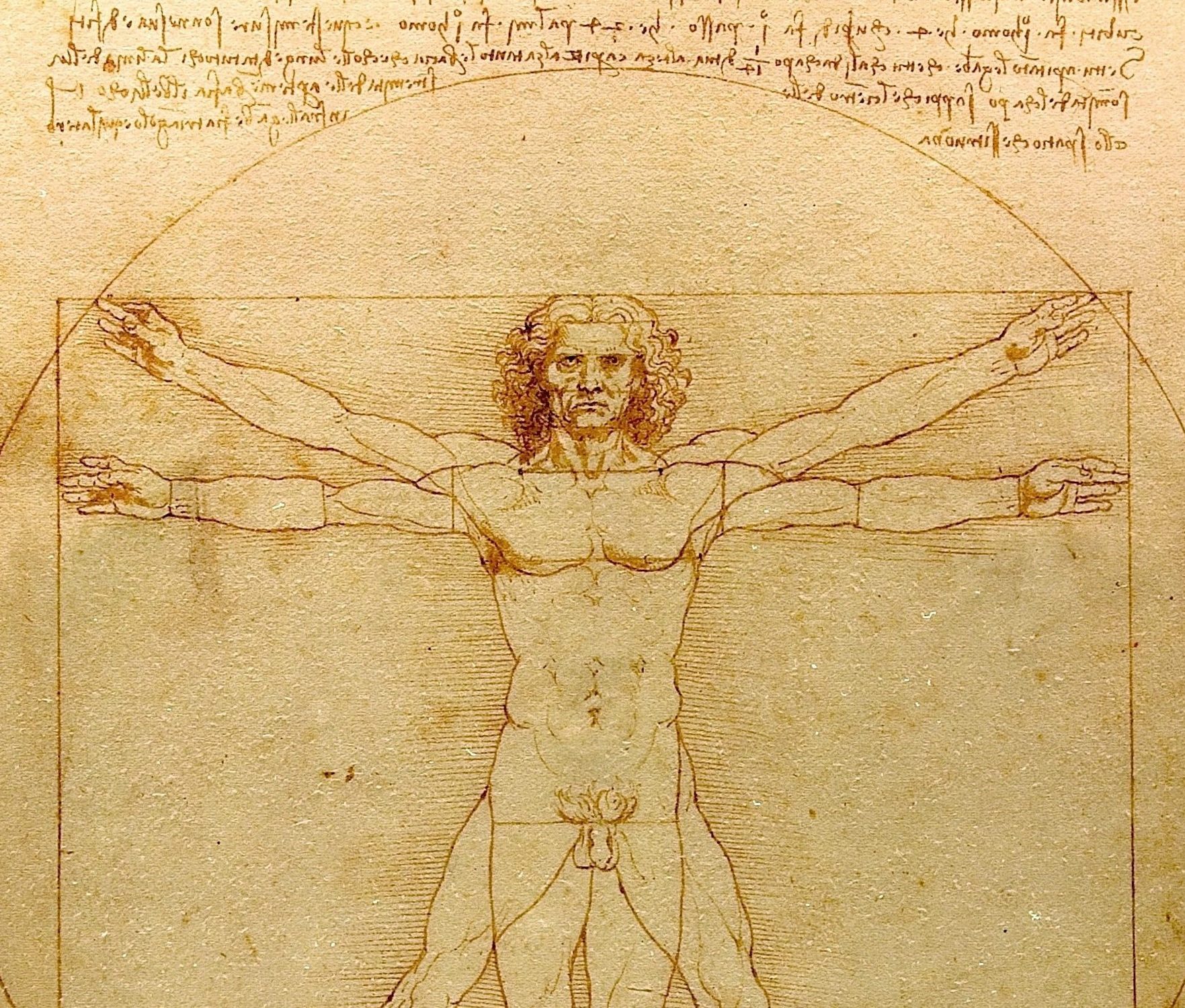

Leonardo da Vinci’s famous drawing the “Vitruvian Man” or “the proportions of the human body according to Vitruvius” (created around 1490) depicts and explains the proportions of what was/is believed to be the ideal male human form. As many readers of fiction might know, the sketch made its way into popular culture through Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code (2003) [I’m not particularly a fan of the novel], in which the naked body of Jacques Saunière, curator at the Louvre in Paris, is arranged spread-eagled on the floor of the Grand Gallery of the museum in the pose of the figure in the drawing. For Leonardo, the geometry of the microcosm that was the body was analogous to the geometry of the macrocosm that was the universe.

The name of the drawing is derived from the work of Marcus Vitruvius Pollio (c. 80 BC – c. 15 BC) – the Roman author, architect, civil engineer and military engineer – known chiefly for his multi-volume architectural treatise De Architectura (written between 30 BC and 15 BC). A guidebook for construction projects, it was executed under the patronage of and dedicated to emperor Caesar Augustus (63 BC – 14 AD), founder of the Roman empire and great-nephew of Julius Caesar.

De Architectura is divided into ten parts:

- Town planning, architecture or civil engineering in general, and the qualifications required of an architect or the civil engineer

- Building materials

- Temples and the orders of architecture

- ‘continuation of book III’

- Civil buildings

- Domestic buildings

- Pavements and decorative plasterwork

- Water supplies and aqueducts

- Sciences influencing architecture – geometry, measurement, astronomy, sundial

- Use and construction of machines – Roman siege engines, water mills, drainage machines, Roman technology, hoisting, pneumatics

Here, I share two extracts.

Vitruvius on the education of the architect:

The architect should be equipped with knowledge of many branches of study and varied kinds of learning, for it is by his judgement that all work done by the other arts is put to test. This knowledge is the child of practice and theory. Practice is the continuous and regular exercise of employment where manual work is done with any necessary material according to the design of a drawing. Theory, on the other hand, is the ability to demonstrate and explain the productions of dexterity on the principles of proportion.

It follows, therefore, that architects who have aimed at acquiring manual skill without scholarship have never been able to reach a position of authority to correspond to their pains, while those who relied only upon theories and scholarship were obviously hunting the shadow, not the substance. But those who have a thorough knowledge of both, like men armed at all points, have the sooner attained their object and carried authority with them.

In all matters, but particularly in architecture, there are these two points:—the thing signified, and that which gives it its significance. That which is signified is the subject of which we may be speaking; and that which gives significance is a demonstration on scientific principles. It appears, then, that one who professes himself an architect should be well versed in both directions. He ought, therefore, to be both naturally gifted and amenable to instruction. Neither natural ability without instruction nor instruction without natural ability can make the perfect artist. Let him be educated, skillful with the pencil, instructed in geometry, know much history, have followed the philosophers with attention, understand music, have some knowledge of medicine, know the opinions of the jurists, and be acquainted with astronomy and the theory of the heavens.

Vitruvius on the harmony and symmetry of bodies and temples:

For the human body is so designed by nature that the face, from the chin to the top of the forehead and the lowest roots of the hair, is a tenth part of the whole height; the open hand from the wrist to the tip of the middle finger is just the same; the head from the chin to the crown is an eighth, and with the neck and shoulder from the top of the breast to the lowest roots of the hair is a sixth; from the middle of the breast to the summit of the crown is a fourth. If we take the height of the face itself, the distance from the bottom of the chin to the under side of the nostrils is one third of it; the nose from the under side of the nostrils to a line between the eyebrows is the same; from there to the lowest roots of the hair is also a third, comprising the forehead. The length of the foot is one sixth of the height of the body; of the forearm, one fourth; and the breadth of the breast is also one fourth. The other members, too, have their own symmetrical proportions, and it was by employing them that the famous painters and sculptors of antiquity attained to great and endless renown.

Similarly, in the members of a temple there ought to be the greatest harmony in the symmetrical relations of the different parts to the general magnitude of the whole. Then again, in the human body the central point is naturally the navel. For if a man be placed flat on his back, with his hands and feet extended, and a pair of compasses centred at his navel, the fingers and toes of his two hands and feet will touch the circumference of a circle described therefrom. And just as the human body yields a circular outline, so too a square figure may be found from it. For if we measure the distance from the soles of the feet to the top of the head, and then apply that measure to the outstretched arms, the breadth will be found to be the same as the height, as in the case of plane surfaces which are perfectly square.

![]()

Utterly amazing.

LikeLiked by 1 person