Located five miles north of San Miguel de Allende in central Mexico, Galería Atotonilco is a treasure trove of Mexican folk art. Owned by ceramic artist, dealer and collector, Mayer Shacter and his wife, writer Susan Page, the gallery is situated next to their home, within an area of eight acres with mesquite trees and frontage on the river Laja.

The neglected property was discovered by the couple in 2001 and transformed by celebrated architects into an unconventional style called “contemporary organic” or “modern baroque”. The setting is a beautiful harmony of ancient and modern Mexico.

Mayer Shacter, originally from California, brings over fifty years of experience in the arts and has travelled all over Mexico. Every piece in his delightful collection is hand-picked with a focus on beauty, innovation and quality craftsmanship. Mayer finds the best artists working today, and then purchases their finest work, often commissioning pieces, so many of the items in the gallery are unique.

I connected with him recently to discuss what he loves about Mexico, the major types of local folk art, the stories behind them, and some of the artisans whom he represents…

Welcome, Mayer. I just loved Galería Atotonilco. Beautiful building in a beautiful location! I’m drawn to the unique syncretism of Mexico, its vibrant energy, and of course, the Day of the Dead. My first question would be this—what attracted you to Mexico?

I grew up in Los Angeles, close to the Mexican border, so as teenagers, we went to Mexico for spring break. Mexico was exotic. It was different. People were cooking fish on the beach, selling colorful wares on the street. It was a great contrast to manicured LA. When I was nineteen, I hitchhiked through Mexico and Latin America for nine months. I was already interested in ceramics and loved discovering the different kinds of ceramics I was seeing.

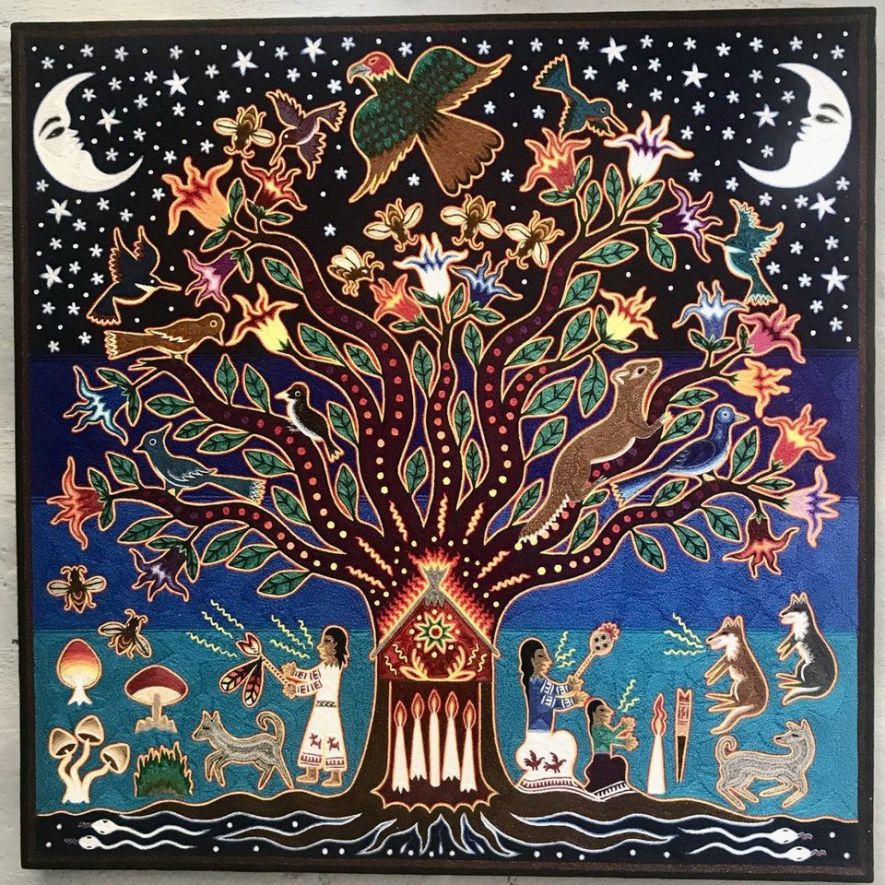

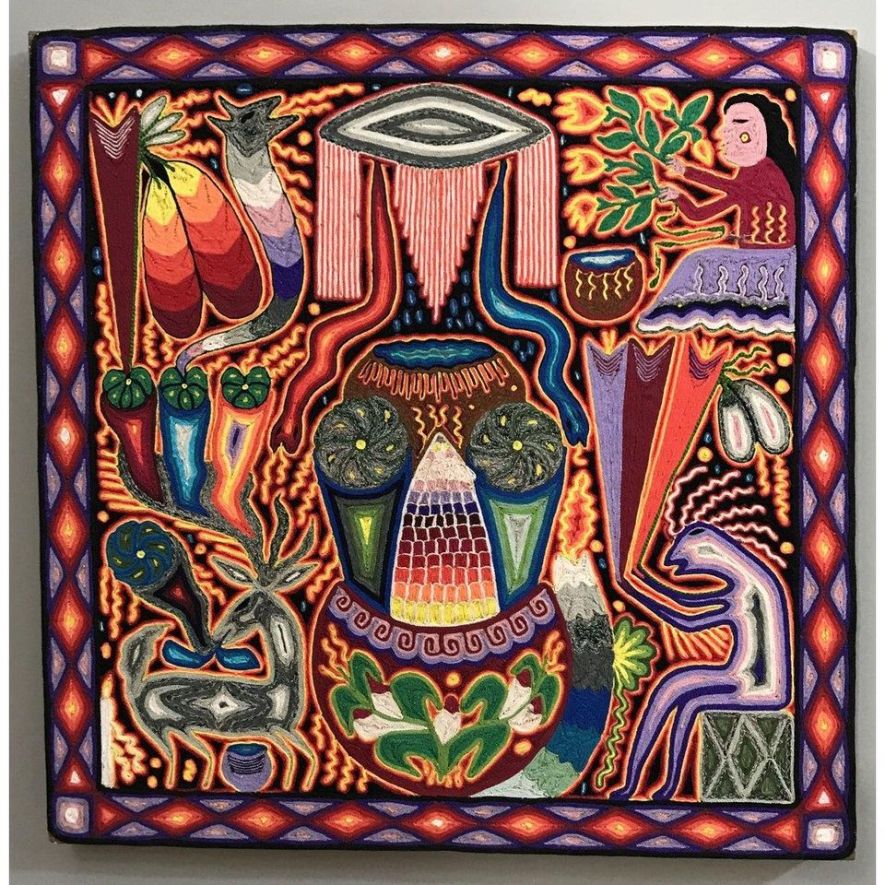

The vibrant culture and values so unlike the money-driven U.S. captivated me and the allure never left me. In 1981, I returned to Mexico with a Huichol yarn painter and his family and became intimately involved with them. Three of the children in the family came to live with us for three years in Berkeley, so they could attend high school in the States.

When my wife and I were looking for a new adventure and happened upon this extraordinary piece of land near San Miguel de Allende, the excitement of living in Mexico took over our lives, and we made it happen very quickly.

It was easy for me to choose a new country as my own because I am only second generation in the States. My grandparents emigrated from Russia in the early 20th century, so I do not have deep roots in the U.S. I was able to select a culture and a country to be my own, one that suits my tastes and my loves. I feel more at home in Mexico than I ever did in the States.

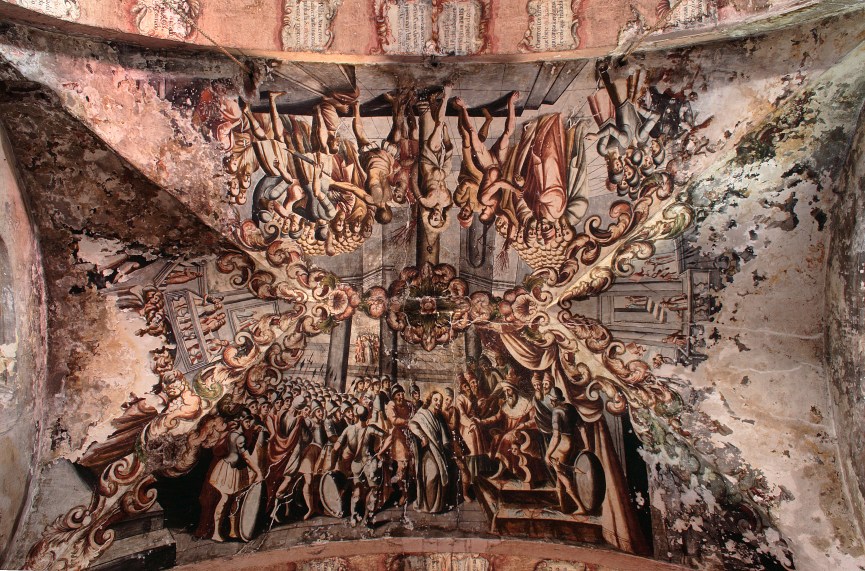

Tell us more about the part of the country where you are based. I read there’s a UNESCO World Heritage site one mile north of the gallery—the Sanctuary of Atotonilco, called the “Sistine Chapel of Mexico.” What else is special and distinctive about the region?

The Mexican Revolution of 1810 that ended in independence from Spain started a few miles from our home. This area, called “Corozon de Mexico” (the heart of Mexico) is steeped in history. The entire town of San Miguel is preserved eighteenth century buildings like magnificent mansions, churches and convents built in the mid 1700s, so the city is utterly charming, and different from other towns that destroyed their colonial-era buildings. The main church on the square in San Miguel is the only gothic-style church in all of Mexico, and it is spectacular.

Largely because of the stunning beauty of its preserved architecture, two artists founded an art institute in San Miguel in the 30s, and the arts developed rapidly here. After World War II, using the G.I. Bill, young men flocked here to study art, initiating a migration of adventurous souls from the U.S. and Canada that continues today.

The foreign community in San Miguel has founded and operates a plethora of non-profit organizations that help to feed and educate youth in poor rural communities around San Miguel and that keep the arts flourishing here including chamber music, opera, jazz, theater, and writing. There is no other city of its size in Mexico that has so much to offer in terms of culture, history, and its gorgeous year-round climate. For three years, Conde-Nast travelers’ survey has voted San Miguel the #1 small city in the world.

How would you introduce the uninitiated to the rich variety of Mexican folk art? What are the most popular forms and types?

Mexico has as great a variety of folk art as any other country in the world. Folk art has its roots in indigenous culture and has been handed down through families for many generations, sometimes hundreds of years. Each artist has acquired a deep knowledge of materials and techniques, a passion for quality, and a high level of skill honed over many years of working and learning from family members or village artists, often since childhood.

Folk art expresses the distinctive soul of the country and culture that is Mexico. Spanish conquerors converted indigenous populations to Catholicism (after they decimated their numbers with diseases and enslavement). However, the native Mexicans never abandoned their cherished traditions and beliefs; they simply incorporated the Christian story into their centuries-old traditions, mythologies, religions, and art. Saints in Mexican Catholicism closely resemble the gods they had in their indigenous culture. Mexico’s beloved and ubiquitous Virgin of Guadalupe is simply a Catholic-acceptable version of the goddess Tonantzin: Mother Earth, the Goddess of Sustenance, the Great Mother. According to tradition, the Virgin of Guadalupe first appeared on the hill of Tepeyac, which was the site of the pre-Hispanic worship of Tonantzin.

Folk art is entirely regional. Artists in one village all work in the same traditional craft, and nowhere else in the world will you find that style of work. It would be rare to find a woodcarver in a town where the tradition is ceramics. The subjects portrayed in folk art are usually scenes of simple country life, nature, mythology, Day of the Dead, religion, traditional arts, and humor. A common theme is duality: sun and moon, male and female, life and death, day and night – the yin/yang of Mexican culture. The mermaid embodies both land and sea and so is a symbol of the universe. Above all, folk art is an expression of the history and the heart and soul of the Mexican people and their distinctive culture. Some examples:

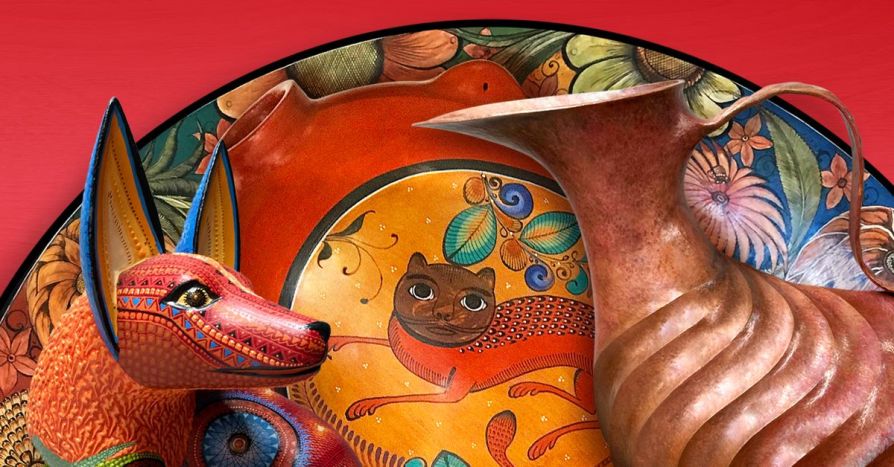

In Tonalå, Jalisco, with a rich source of clay nearby, artists have been creating ceramic art for thousands of years. They paint their vases and chargers, using highly skilled brushwork and painting scenes from nature and everyday life. In the ancient style, they do not glaze the work but burnish it to bring it to a high shine.

In Santa Cruz de las Huertas, the town produced sewer pipe and roof tiles, until one enterprising artist around 1900 began making figures from the clay. Now several families there create imaginative scenes, animals, and figures, many with a humorous or surreal quality, like a pig playing a violin, a pregnant chicken, a bull dancing with a mermaid, or Mary, Jesus, Joseph, and the three wise men riding in a car.

In an ancient indigenous town, a four-hour drive off any main highway, high in the remote mountains of Guerrero, artists have been creating lacquer items for thousands of years. Lacquer in that town predates the arrival of the Spanish and of the Manila galleons that brought oriental lacquer to Mexico. Today, the artists grow gourds and create their own lacquer from chia oil and mineral powders, which they grind themselves and impregnate with naturally sourced dyes. Then with astonishing skill, they decorate the gourds with handmade brushes.

Members of the famous Linares family in Mexico City are widely recognized as the finest paper maché artists in Mexico, and their work is highly sought after by collectors. They have carried paper maché to a high art and may need several months to complete a single decorated skull, fanciful animal, or “alebrije”.

The enormous variety of folk art in Mexico, besides lacquer and many forms of ceramics, includes woodcarving, paper maché, copper, silver, textiles, yarn paintings, baskets, and more.

Who are some of your most accomplished artisans?

The father and son team of Angel Ortiz and José Angel Ortiz create some of the finest ceramic work found anywhere. Just as talented a ceramic artist is Luis Cortez, who works with his wife, Irma. A very fine Huichol yarn painter is Gonzalo Aarillo Hernandez. Woodcarvers Franco Ramirez and his wife Nellie do beautiful, innovative work and sometimes work in large scale. The finest paper maché creations are made by the Linares family of Mexico City.

These brief examples of art work and artists barely scratch the surface of the very large numbers of accomplished folk artists working today all over Mexico, carrying on the traditional work of their family or village, having developed and honed their skills over many years.

How do you find artisans? And what do you look for when selecting them?

I am immersed in the world of folk art and have many friends among the artists. They introduce me to other artists. I may go to a town with a reputation for a certain type of work, and I just have to start asking where artists’ studios might be. This can be like a treasure hunt. Sometimes when artists hear that I am in town and that I am buying, word travels fast and they all come out of their homes with work to show me. Now that the gallery is fifteen years old, I have deep and loving friendships with many of the artists and their families.

What I am seeking in the work is quality craftsmanship and a unique vision. I like to see work that both preserves the village traditions but also shows imagination and innovation. I look for artists with whom I can develop a long-term relationship, who will produce work consistently and in sufficient quantity and where we will be able to nurture a mutually respectful bond.

An important aspect of my gallery is that I am there to promote the artist, not only the work. My goal is to help these families maintain a sustainable lifestyle. I show photos of the artists next to their work and encourage travelers to visit villages and studios.

How do pre-Hispanic and European influences come together in Mexican folk art? Give us a few examples.

Pottery: The tradition of burnished pottery in Tonalá is 3,000 years old. Pre-Hispanic artists made burnished clay items with great skill. When the Spanish arrived, they introduced the potter’s wheel, though much of the work in Tonalå is still hand-built or created with molds. The Spanish also introduced new forms and designs. For example, the double-headed eagle is a European symbol, and Moorish influences appear in some work after the Spanish arrived.

Textiles: Indigenous Mexicans were excellent weavers using the back-strap loom and natural fibers like cotton, sisal, and dried grasses or palm fibers. The Spanish introduced both the treadle loom and wool. Both of these changes allowed weavers to create elaborate and breathtakingly spectacular serapes, a tradition that flourished in Mexico until about 1950. The tradition died out because the time, skill, and labor involved in creating a serape made them too expensive for the general market.

Lacquer: Though lacquer was produced in several Mexican communities long before imports of oriental lacquer appeared, still it is possible to see oriental influences in Olinala lacquer designs. Artists adopted, not so much the subject matter of oriental lacquer, but the style and color of oriental designs. For example, they increased their use of red lacquer, and they incorporated the oriental idea of perspective, even in simple designs.

Iron Work: The Spanish brought with them the apprenticeship method of teaching. Spanish craftsmen took indigenous artists as apprentices, who were able to expand and strengthen their skills. The Spanish made exquisite locks and hinges for the trunks and cabinets made by colonial-era woodworkers. It’s possible to find old Spanish-style hardward with indigenous iconography incorporated into the designs.

Talavera Ware: The only work that is called “Mexican Folk Art” but that does not have its origins in pre-Hispanic, indigenous traditions is the brightly colored, highly decorated pottery that the Spanish brought with them from Talavera, Spain. Mexican artists put their own stamp on the work, which is now produced in great quantities, primarily in Puebla and Dolores Hidalgo.

Quiz: What export from Mexico to Europe and Asia was more valuable than gold or silver from the 16th to the 18th centuries? Answer: Red cochineal dye, made from tiny insects that live on nopal cactus.

Red was an expensive color to produce and red clothes were an important status symbol in both Europe and Asia, with the result that red dyes commanded high prices. The distinctive redcoats of the British Army were dyed with cochineal.

Cochineal was introduced from Mexico to Europe following the Spanish conquest of Mexico in 1519. Cochineal produced a deeper and longer lasting red than dye produced from madder root. Therefore the cochineal red dye was highly valued. The Spanish kept the source of cochineal secret, and cochineal was thought to be a plant seed for nearly 200 years. In the nineteenth century, when artificial dyes were developed, red dyes became cheap to produce and cochineal was no longer valued, though it is still widely used by textile and rug weavers in Mexico who value the authenticity of traditional methods and work to be sure that these ancient skills and materials are not lost.

Intellectually or spiritually, what are the most important insights that you have gained over the years by engaging with Mexican culture?

It is remarkably different to live in a culture that is not driven by money. Mexicans need enough to live on, but far more than money, they value family, fiestas, and food. Their lives are built around their loyalty to family and their passion for their elaborate and colorful festivals.

Philanthropy is almost unknown in Mexico. They will spend every penny on the all-important fifteenth birthday celebration for girls in the family. But giving money to strangers outside the family, for whatever good it might do, is a weird concept to them.

Saving face is of utmost importance to Mexicans. If you ever insult or become angry with a Mexican, even a good friend, it can end the relationship for a lifetime. You have to be thoughtful about how you are going to engage with someone whose behavior you would like to change. You can never embarrass a Mexican or put someone down. These are wonderful skills to acquire.

Arrazola, Oaxaca. © Galería Atotonilco

The flip side of that is that a Mexican friend is a true heart relationship. Friendships here are full of love, may be deeply personal and honest, and above all loyal. Mexicans are exceptionally warm people, kind, generous, and loving. For example, medical care here is light years away from the quick, busy consults you get from busy U.S. doctors. A doctor appointment here can last an hour or more. Nursing care in hospitals is full of genuine caring and concern.

Do you have to be a collector or have a Mexican theme to your home or to a certain room for folk art to fit into your décor?

Because of the huge variety of Mexican folk art, much of it greatly enhances any decorative scheme. From spectacular ceramics to elegantly crafted copper vases and sculptures to spectacular textiles for wall hangings, to dazzling lacquer gourds, to exquisitely painted and gestural woodcarvings, a piece can add visual beauty and interest to any decor from modern to traditional. These works of art are conversation pieces that can add a visual focus and bring color and beauty to any room.

Of course, many people do find that, once they become interested in a type of folk art, they want to add to their collection, to support a certain artist or village, and to add richness to their lives by becoming immersed in the Mexican story.

Links: Store (galeriaatotonilcostore.com) | Website (galeriaatotonico.com) | Facebook (www.facebook.com/GaleriaAtotonilco) | Twitter (twitter.com/GAtotonilco) | Instagram (www.instagram.com/galeria_atotonilco) | Pinterest (www.pinterest.com.mx/GAtotonilco/_created)

One thought on “On Mexican Folk Art and a Culture not driven by Money: A Talk with Mayer Shacter, Galería Atotonilco”

Comments are closed.