As a huge fan of fairytales, I hope to explore their many evident and latent meanings – moral, psychological, religious, ecological, sexual – on this blog over the months and years. There is so much interesting literature available on the subject, it is difficult to decide on a point of departure. There’s J. R. R. Tolkien (Essay “On Fairy-stories” in his collection Tree and Leaf) and G. K. Chesterton (Chapter “The Ethics of Elfland” in his spiritual autobiography Orthodoxy). Then the works of recent scholars like Bruno Bettelheim (The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales) and Marina Warner (Once Upon a Time: A Short History of Fairy Tale).

I think, for now, I would like to concentrate on an essay called “On Three Ways for Writing for Children” by Oxford don, novelist, theologian and broadcaster C. S. Lewis (1898–1963) – included in his very readable On Stories: And Other Essays on Literature – that contains invaluable insights on the topic. It was originally read to the Library Association and published in their Proceedings, Papers and Summaries of Discussions at the Bournemouth Conference 29th April to 2nd May 1952.

Lewis begins by directly describing and differentiating between the three approaches a writer of children’s literature might adopt. One, according to him, is a bad way. Two are good. His own is the third. First, the bad way:

I came to know of the bad way quite recently and from two unconscious witnesses. One was a lady who sent me the MS of a story she had written in which a fairy placed at a child’s disposal a wonderful gadget. I say ‘gadget’ because it was not a magic ring or hat or cloak or any such traditional matter. It was a machine, a thing of taps and handles and buttons you could press. You could press one and get an ice cream, another and get a live puppy, and so forth. I had to tell the author honestly that I didn’t much care for that sort of thing. She replied, ‘No more do I, it bores me to distraction. But it is what the modern child wants.’ My other bit of evidence was this. In my own first story I had described at length what I thought a rather fine high tea given by a hospitable faun to the little girl who was my heroine. A man, who has children of his own, said, ‘Ah, I see how you got to that. If you want to please grown-up readers you give them sex, so you thought to yourself, “That won’t do for children, what shall I give them instead? I know! The little blighters like plenty of good eating.” In reality, however, I myself like eating and drinking. I put in what I would have liked to read when I was a child and what I still like reading now that I am in my fifties.

The lady in my first example, and the married man in my second, both conceived writing for children as a special department of ‘giving the public what it wants.’ Children are, of course, a special public and you find out what they want and give them that, however little you like it yourself.

The second way, which Lewis thinks is the style of Lewis Carroll, Kenneth Grahame and Tolkien, may initially seem like the first method. But the resemblance is superficial. Lewis explains:

The printed story grows out of a story told to a particular child with the living voice and perhaps ex tempore. It resembles the first way because you are certainly trying to give that child what it wants. But then you are dealing with a concrete person, this child who, of course, differs from all other children. There is no question of “children” conceived as a strange species whose habits you have “made up” like an anthropologist or a commercial traveler. Nor, I suspect, would it be possible, thus face to face, to regale the child with things calculated to please it but regarded by yourself with indifference or contempt. The child, I am certain, would see through that. In any personal relation the two participants modify each other. You would become slightly different because you were talking to a child and the child would become slightly different because it was being talked to by an adult. A community, a composite personality, is created and out of that the story grows.

Now the third way, which Lewis says he is most comfortable with, consists in writing a children’s story because a children’s story is simply “the best art-form” for something the writer may have to say – just as a composer might write a Dead March not because there was a public funeral in view but because certain musical ideas that had occurred to him went best into that form. Herein the writer writes naturally, effortlessly, wholeheartedly.

Within the genre of children’s literature, the sub-species that happens to suit Lewis best is the ‘fantasy’ or what we can loosely call the ‘fairytale’. But a man who admits that “dwarfs and giants and talking beasts and witches are still dear to him in his fifty-third year” is “less likely to be praised for his perennial youth than scorned and pitied for arrested development.” Lewis’s defence against these charges consists of multiple propositions.

On the question of adulthood and childishness, maturity and immaturity, he writes:

Critics who treat adult as a term of approval, instead of as a merely descriptive term, cannot be adult themselves. To be concerned about being grown up, to admire the grown up because it is grown up, to blush at the suspicion of being childish; these things are the marks of childhood and adolescence. And in childhood and adolescence they are, in moderation, healthy symptoms. Young things ought to want to grow. But to carry on into middle life or even into early manhood this concern about being adult is a mark of really arrested development. When I was ten, I read fairy tales in secret and would have been ashamed if I had been found doing so. Now that I am fifty I read them openly. When I became a man I put away childish things, including the fear of childishness and the desire to be very grown up.

On the issue of growth and continued interest in the stories of one’s childhood, he says:

The modern view seems to me to involve a false conception of growth. They accuse us of arrested development because we have not lost a taste we had in childhood. But surely arrested development consists not in refusing to lose old things but in failing to add new things? […]

I now enjoy Tolstoy and Jane Austen and Trollope as well as fairy tales and I call that growth: if I had had to lose the fairy tales in order to acquire the novelists, I would not say that I had grown but only that I had changed. A tree grows because it adds rings: a train doesn’t grow by leaving one station behind and puffing on to the next.

On escapism:

The real victim of wishful reverie does not batten on the Odyssey, The Tempest, or The Worm Ouroboros: he (or she) prefers stories about millionaires, irresistible beauties, posh hotels, palm beaches and bedroom scenes—things that really might happen, that ought to happen, that would have happened if the reader had had a fair chance. For, as I say, there are two kinds of longing. The one is an askesis, a spiritual exercise, and the other is a disease.

On the impact of fairy tales on the imagination, he beautifully elaborates:

In a sense a child does not long for fairy land as a boy longs to be the hero of the first eleven. Does anyone suppose that he really and prosaically longs for all the dangers and discomforts of a fairy tale?—really wants dragons in contemporary England? It is not so. It would be much truer to say that fairy land arouses a longing for he knows not what. It stirs and troubles him (to his life-long enrichment) with the dim sense of something beyond his reach and, far from dulling or emptying the actual world, gives it a new dimension of depth. He does not despise real woods because he has read of enchanted woods: the reading makes all real woods a little enchanted.

—-

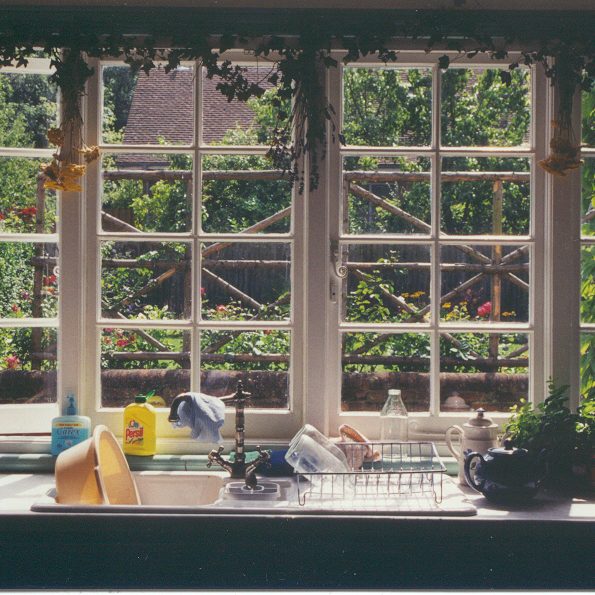

Image Credit:

Featured: View from the kitchen of C. S. Lewis’ house, The Kilns in Oxford by User “jschroe”, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

—-

![]()

Great piece! I still love children’s stories. I’m miss my kids being little and reading to them. Some really good quotes too, I enjoyed this 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! 🙂 I love C. S. Lewis’s simple but poetic way of explaining things.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Me too!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I still read and even write children’s stories…they are my first love and as Lewis says it came from the books read to me and that I read as a child.

George MacDonald had a great influence on many children’s writers and Lewis regarded him as his “master” in storytelling.

I am reading At the Back of the North Wind at the moment…again!

Great post!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! 🙂 I have heard a lot about George MacDonald – especially his “Princess and the Goblin”. Haven’t read it yet. Look forward to reading!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Everything he wrote is wonderful. Enjoy!

LikeLiked by 1 person