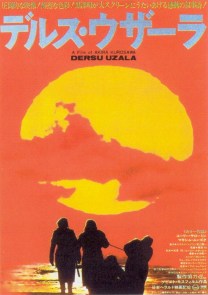

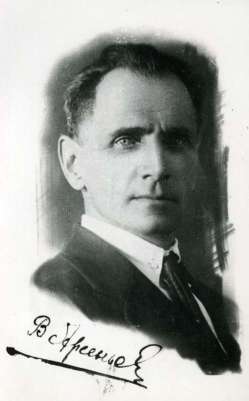

Described as “a testament to the value of friendship and the indomitability of the human spirit”, the 1975 Soviet-Japanese co-production Dersu Uzala (Amazon, Netflix) was the first non-Japanese-language film of celebrated Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa (1910-1998), who is known to have masterfully engaged with everything from local swordfighting to Shakespearean plays. Most famous for his highly acclaimed movies Rashomon (1950), Ikiru (1952), Seven Samurai (1954), Kagemusha (1980) and Ran (1985), Kurosawa was voted “Asian of the Century” in a poll conducted by the news magazine Asiaweek (1975-2001) in 1999. And his Seven Samurai was ranked at no. 1 in a list of “The 100 Best Films of World Cinema” compiled by British film magazine Empire in 2010.

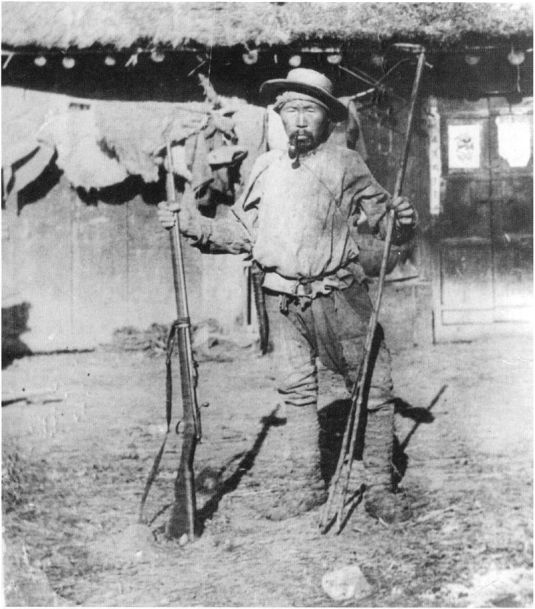

The tale begins in the year 1910, with Arseniev looking for the grave of a friend he’d buried three years earlier in a forest that is being felled for development. The narrative then goes back to 1902 – to the time of Arseniev’s first major expedition in the Ussuri area. Dersu, whom he and his fellow soldiers encounter in the wilderness, at first appears naive and eccentric but is soon able to demonstrate his intelligence. He saves Arseniev’s life twice, once in a blizzard and then during the second expedition in 1907, over the rapids. The captain invites his savior to his city Khabarovsk, but the latter is ill at ease within the comforts of civilisation, progress and modern life. He prefers to return to untouched nature with its many dangers. The most moving image of the film perhaps is the end scene wherein a sorrowful Arseniev stands with his head bowed before his friend’s remains – and with much love and respect simply lets out a low “Dersu…”

Dersu’s magnanimity is nourished by his perception of the essential spirituality of nature. He talks to the fire and to wind and water as if they were people. A soldier laughs and asks him why, and Dersu replies because they are alive. Angry fire, water, and wind are frightening, he says. They are powerful men. A strong breeze suddenly appears, whipping leaves across the frame, as if in answer to his words. Earlier, in a magnificent image, Dersu and Arseniev stood on a vast plain, framed between the moon on their left and a fiery setting sun on their right, humans and celestial bodies alike flattened by the long lens into a single plane of space. It is an image of great mystery and serenity. As they contemplate the heavens, Dersu explains that the sun is the most important man because if he dies everything else dies, too. He initiates Arseniev into the secrets of the universe. The other Kurosawa heroes were in touch with important social and moral imperatives, but Dersu is connected to cosmic truths, and it is Arseniev’s blessing to have known him briefly.

~ As mentioned in The Warrior’s Camera: The Cinema of Akira Kurosawa (1991/1999, Princeton University Press)

Dersu Uzala is a lovely film on the meeting of cultures and two very different lifestyles. Its natural – and stunning – cinematography will be appreciated by those who are bored with the special effects of present-day action movies. Here, there are no green screens and matte paintings. Just pure forests and mountains and snow. Here, there is real adventure.

![]()

![]()

Here is the English trailer for the film.

The entire movie is available with English subtitles in two parts from Mosfilm. Watch it here and here. Watch a scene below:

And now – Dersu Uzala winning an Oscar for the Best Foreign Language Film in 1976.

—-

Further Reading:

Akira Kurosawa: Master of Cinema (2010) by Peter Cowie

Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Cinema (2016) by Peter Rollberg

—-

Image and Video Credits:

Featured poster and subsequent clips from Dersu Uzala are property of Daiei Film/Mosfilm/New World Pictures. Used for illustrative, educational and entertainment purposes only. No copyright infringement intended.

—-

![]()

How interesting. Unfortunately the films don’t play when I click on them (from UK) Perhaps they will if I come back to them later.

LikeLike

Back now and they work. Shall watch the whole movie when I get time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There are many Soviet classics available!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Admirable!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very very profound film, with many haunting scenes. One of my favorite films.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wish more people knew of it!

LikeLike

one of my favorite scenes in any film is the scene when Dersu berates the soldiers for not only wasting bullets, but also a perfectly good glass bottle. the outcome from his actions is just beautiful.

there are few characters as profound & well developed as Dersu in the history of film.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Truly a masterpiece!

LikeLike