Mentioned by Virgil, Sophocles and others, Laocoön (from Greek and Roman mythology; pronounced lay-AW-koo-on) was a Trojan priest who tried to alert his people of the stratagem of the Trojan Horse (giant wooden horse with warriors hidden in the belly) that was used by their enemies the Greeks (sometimes called “the Achaeans”) to enter and destroy the city of Troy. (Read about the Trojan War here.)

Laocoön and his two sons Antiphantes (older) and Thymbraeus (younger) were strangled and killed by sea serpents sent by the gods/goddesses – in some versions, it is Athena, in others, Apollo. The events vary considerably across different accounts.

In art, the figure has gained fame largely on account of a statue excavated in 1506 near the church of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, on display today at the Vatican Museums. The Laocoön Group or Laocoön and His Sons contains almost life-size marble sculptures of the father and sons.

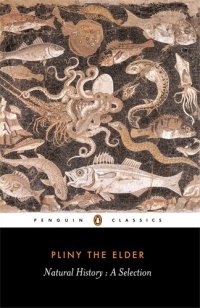

The Roman writer Pliny the Elder (23 AD-79 AD) referred to the group in his Natural History. At 36.37, he writes, “It is a work to be set above all that the arts of painting and sculpture have produced. Out of a single block of marble, the consummate craftsmen of Rhodes – Hagesander, Polydoros and Athenadoros – at the behest of council designed a group of Laocoön and his sons, with the snakes entwined around them all.”

The sculpture on the whole is, according to the British classicist Nigel Spivey (from the University of Cambridge), “the prototypical icon of human agony in Western art”. The first figure to respond to the artwork was Cardinal Jacopo Sadoleto, who was present during the excavation and found Laocoön’s scream to be the “heroic groaning of a wounded man”. Later, J. J. Winckelmann (1717–1768), a German art historian, wrote: “He lets out no heaven-rending scream…rather an anxious, heavy-burdened sigh…his misery cuts us to the quick, but we yearn for the hero’s exemplary strength to endure it.” Spivey goes on to contrast Laocoön’s agony with that of Christ. Because Christ was/is believed to have died to redeem the world, his passive suffering – and that of Christian martyrs subsequently – was/is translated into sublime victory. But the “Suffering Servant” had absolutely no claim to honour in any of the moral systems devised by the Greeks and Romans. There, pain had no great power. Sacrifice didn’t make the world a better place. Loss was useless. Catastrophe was final. Classical Greece was the birthplace of the literary genre we call “tragedy”, of which Laocoön is a true and terrifying icon. [More in Enduring Creation: Art, Pain, and Fortitude (2001, University of California Press)]

Here is a short video from Smarthistory on the sculpture:

—-

Further Reading:

The Art of Greece and Rome (2004) by Susan Woodford

The Greek Body (2009) by Ian Jenkins

—-

Image Credits:

Featured: Detail of Laocoön and his Sons by User “Giulio Menna”, CC BY 2.0, Flickr

—-

![]()

Keep up the good work. I am reminded again of the insights the ancient Greeks had into the human situation. And sometimes my own.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks a lot! I’ve read very little Greek lit – will certainly be reading more.

LikeLike

Marvelous!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks. I’ve seen this mentioned in art histories, never knew what it was. Now put faces to the name.

LikeLiked by 1 person