Running from September 8 through October 21, 2023 at James Cohan Gallery in New York is “The Venus Effect” by American artist Jesse Mockrin that looks into the representations of women in Western art history—the display of the female body and the direction of the feminine gaze. In this collection of sumptuous paintings concepts from the past are reworked for our time.

Mockrin writes: “Venus, Susannah, Bathsheba, Mary Magdalene—as well as witch, seductress, and sinner—are examples of the contradictory cultural narratives about women that are woven into Western European art history. The female body is the favoured metaphor for lust, the life cycle and even painting itself. To me, these examples all pile on top of each other until the female body, like Atlas holding up the world, is left struggling under the weight of all that has been ascribed to it.”

Extracting details from European Old Master paintings, Jesse Mockrin recontextualises cultural narratives and art historical motifs to speak to the present. In “The Venus Effect”, Mockrin explores historical representations of women with mirrors, ranging from scenes of the toilette to biblical and mythological narratives of reflection.

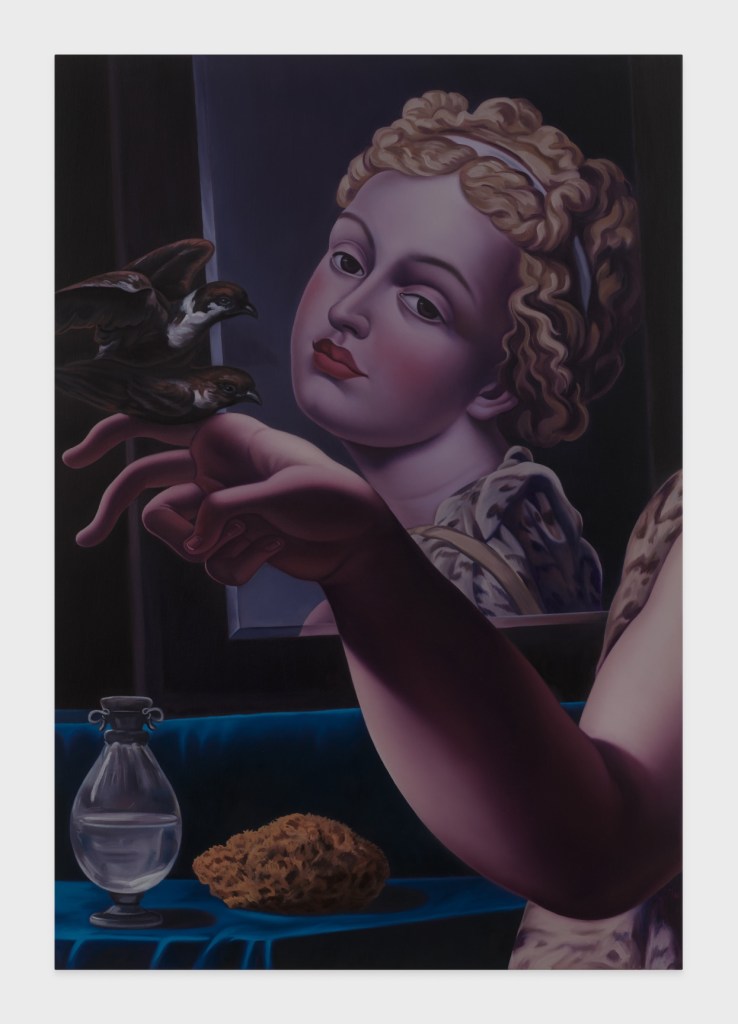

The Venus effect, named for the art historical tradition of images that depict Venus gazing into a mirror, is a perceptual phenomenon wherein the viewer is fooled into believing that Venus is looking at her own reflection. In reality, her line of sight in the mirror connects with the viewer of the painting or the painter who created it. Mockrin sees this as an apt metaphor for these historical paintings themselves, which profess to portray women’s self-obsession, but instead depict a female subject gazing adoringly at the male painter who fashioned her.

For centuries, images of women painted by men have depicted women’s beauty and nudity in the service of revealing an innate feminine vanity, greed, or wantonness. Mockrin reveals whose narcissism and gratification is truly on display. Through the artist’s contemporary feminist lens, the mirror becomes the tool through which her sitters recognise themselves as both the object of desire and a powerful subject whose agency is antithetical to their original narratives.

Mockrin often works in a diptych or triptych format, with painted bodies truncated by the edge of one frame extending into the composition of another. These visual pauses cast the artist’s figures into a realm within which the boundaries of time, gender, and the body dissolve, transforming her subjects into hybrid sites of layered meaning. In her monumental diptych The lover and the beloved, 2023, Mockrin juxtaposes figures from two depictions of Rinaldo and Armida – one painted by Tiepolo in 1742-45, and the other by Nicolas Mignard in the mid-1650s. The subject of both panels is the story of the Christian crusader Rinaldo and the Saracen sorceress Armida, who has seduced Rinaldo and spirited him away to her magical garden. In the 16th-century epic poem by Torquato Tasso, Rinaldo – like Odysseus before him – is a hero led astray by a sexually powerful (and thus dangerous) woman, who must be freed by his fellow soldiers. Mockrin places her figures in mirrored poses.

Rinaldo lounges submissively at Armida’s feet, gazing up in naked adoration – a narrative moment in which the standard gender roles are reversed. Mockrin seeks to complicate the binary messages of the original paintings, instead insisting on multiplicities of interpretation, desire, and desirability. The works in this exhibition highlight the long history of constructed narrative that has painted women into

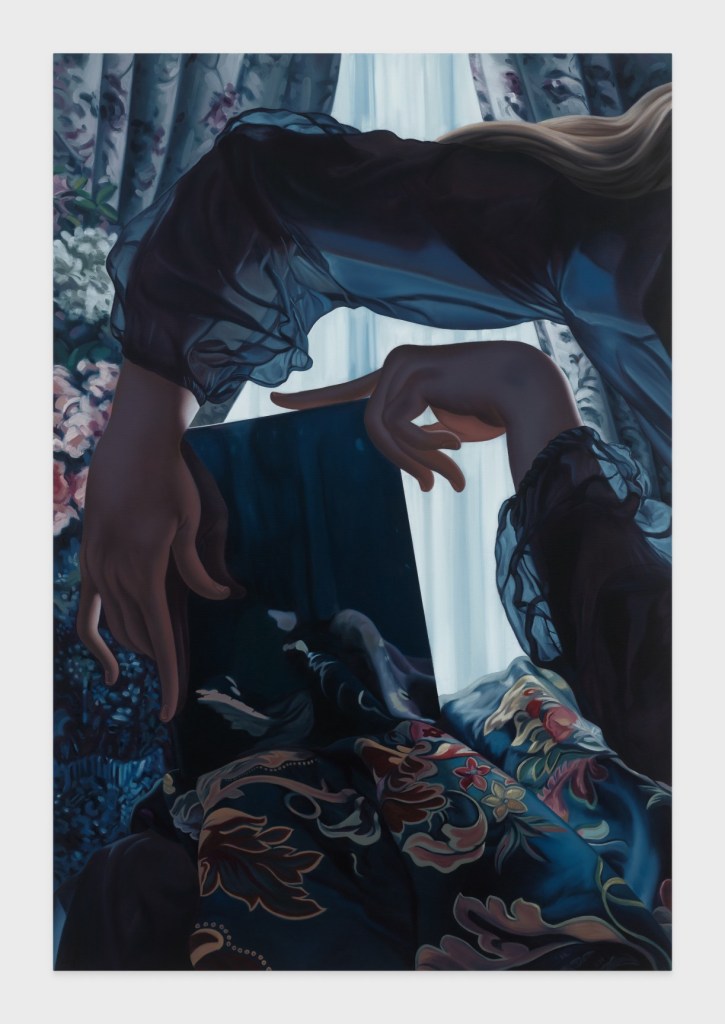

specified roles. The figures in Mockrin’s paintings are flattened into an artificially constructed plane, pressed in upon by fabric, flowers, patterns and decoration – stereotypical symbols of femininity. Despite their spatial restraints, these figures touch, grasp, gaze, and command. In Echo, 2023, the sumptuous details that surround Bathsheba and Susannah are drawn from myriad sources, and reflect Mockrin’s omnivorous approach to building these fictive spaces that collapse the historical and the contemporary. The artist first encountered the backdrop of Bathsheba’s toilette in an interior set from the TV series Gentleman Jack, which centers on the true story of lesbian 19th-century landowner and industrialist Anne Lister. In setting her monumental biblical figures within this space, Mockrin suggests a more complex reality of female desire existing outside the male gaze.

Mockrin’s paintings are characterised by a tightly controlled surface and a sense of internal light that seems to diffuse from within the bodily forms to their smooth edges. The artist builds at least three layers of paint on the skin of her figures, blended to obscure any visible brushstroke. That these hyper-even, eerily bloodless complexions suggest plaster or AI-generated Instagram filters rather than human flesh is an intentional extreme. “I feel we see it in plastic surgery all the time,” Mockrin notes. “The pursuit of the ideal pushes past beauty into the uncanny.” In Herself unseen, 2023, Mockrin plumbs this strangeness to reveal a timeless ambivalence towards one’s own reflection. A mirror evokes vanity as much as it allows for self-contemplation. As Mockrin writes, “‘Herself unseen’ refers to the fact that despite [the sitter] viewing her image in not one but two mirrors, the parts of her that matter most remain unseen by the artist, by us, and possibly by herself.”

Jesse Mockrin (b. 1981, Silver Spring, MD) has been the subject of solo exhibitions at the Center of International Contemporary Art of Vancouver; Canada, Night Gallery, Los Angeles; Nathalie Karg Gallery, New York; and Galerie Perrotin, Seoul. Her work was most recently featured in the 16th Lyon Biennale of Contemporary Art, and she has been included in group exhibitions at the Dallas Museum of Art, Texas; The Bunker, West Palm Beach; Perrotin, Paris; Mrs., Queens; James Cohan, New York; Friends Indeed, San Francisco; SPURS Gallery, Beijing; and Almine Rech, Brussels, among others.

Her work is in the permanent collections of the Art Institute of Chicago, IL; Dallas Museum of Art, TX;

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, CA; Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, CA; Museum of

Contemporary Art, San Diego, CA; Santa Barbara Museum of Art, CA; Rubell Collection, Miami, FL; Aurora Museum, Shanghai, China; Hans-Joachim and Gisa Sander Foundation, Darmstadt, Germany; KRC Collection, Voorschoten, Netherlands; and the Xiao Museum, Rizhao, China, among others. Mockrin lives and works in Philadelphia, PA.

Links: Website (jessemockrin.com) | Instagram (www.instagram.com/jessemockrin)

.

.

.