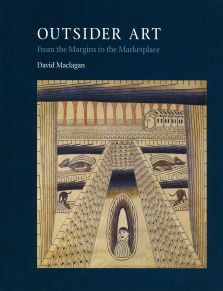

“The term ‘Outsider Art'”, writes Gloucestershire-based artist and lecturer David Maclagan,

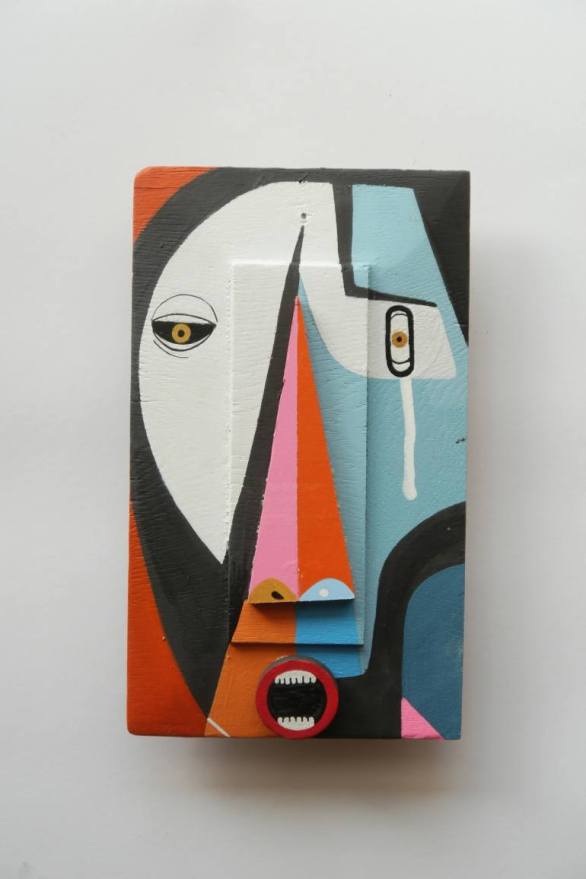

Painter and sculptor Martin Gerstenberger (born in 1981 in Landshut, Germany) – although hardly a marginal figure himself – is heavily inspired by the spirit of the movement. He likes the weird work of outsider artist Henry Darger (1892-1973) [mentioned in this blog post on loneliness and art], a Chicago janitor who left behind a 15,000-page single-spaced manuscript and hundreds of paintings depicting children (and, it is complicated and unsettling, quite a lot of violence) in a fantastical universe.

Martin has other big influences as well. Some of them are the provocative art of Martin Kippenberger, the funky colouring of Tobias Rehberger, the cool graffiti style of Os Gemeos. On his combining of diverse artistic styles, he says, “My work reflects the modern way of life in an ironic way. I tend to merge things the way capitalism absorbs all rude and natural forms of living.”

Whether sculpture or painting or mural or anything else, all of Martin’s creations are made up of basic and ordinary components. Humour is present throughout. “My pictorial narrative technique is that of the stream of consciousness,” he explains. “Protagonists, landscapes and motifs rising from the stream of consciousness are cut out of their larger context and intertwined in free association with new content and figures. A wondrous universe of styles, time frames, social developments opens up before the viewer. Often seemingly naive, sometimes expressive, sometimes wild.”

“Hopefully,” he continues, “I will get the viewer to detect some style-, form- and thematic-elements that they have already seen somewhere else and make them curious about the new arrangement they might find in my work. Furthermore, they might see the importance of reflecting on objects and stories from the past and attempt to transfer them into the presence or the future – that is what culture is about.”

As an artist, Martin feels he must perform a three-fold job. “First,” he says thoughtfully, “an artist has to generally keep alive a behaviour that can pronounce the difference between a human being and an animal, that is, he must simply do culture. Secondly, he is a translator of the circumstances of the time he is living in and must interpret them in his way. Third, he has to play the part of a stranger…as being an artist means living an alternative way of live.”

Martin’s website is (martingerstenberger.weebly.com). You can also find him on Saatchi Art (www.saatchiart.com/Gerstenberger) and Etsy (www.etsy.com/people/martingerstenberger).

![]()

Really strange!

LikeLiked by 1 person