One of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world, Samarkand (Uzbekistan) is well known for having prospered from its location on the “Silk Road” – a whole network of trade routes connecting China and the Mediterranean between the 100s and 1400s. Caravans towards China were mostly laded with gold, silver, ivory, gems, glass, pomegranates and carrots. While from the other side, came silk, lacquerware, porcelain, jade, bronze and fur. Commerce along the silk routes significantly shaped the civilisations of China, Europe, Arabia, the Indian subcontinent and the Horn of Africa. And Samarkand, on account of its important role, is acknowledged in the UNESCO’s World Heritage List as a “crossroad of cultures”. It has also been a notable centre for Islamic scholarly study.

The city was “invaded by the armies of Alexander the Great, sacked by the troops of the Arab Caliphate, and by the Mongol hordes of Gengis Khan, but it was always reborn from its ashes to become, several times, the capital of the great States of Central Asia. And it remains, thanks to the invaluable wealth of its architecture and pictural patrimony, one of the greatest archaelogical centres ever known.” [Vladimir Lukonin and Anatoly Ivanov in Central Asian Art (2015)]

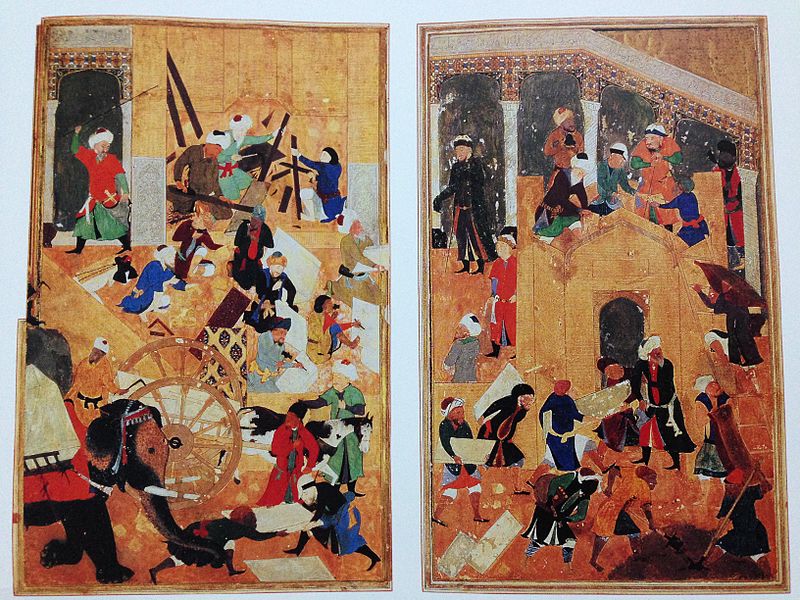

In the 14th century, Samarkand became the capital of the Timurid Empire of Persia and Central Asia founded by the Turco-Mongol conqueror Timur (1336-1405) aka Tamerlane. The most powerful and barbaric Muslim ruler of his time, Timur was able to defeat the Ottomans, the Mamluks, the Delhi sultanate and even the Catholic Knights Hospitallers. Timur’s military prowess existed alongside his artistic and cultural vision. The Spanish diplomat Ruy González de Clavijo, ambassador of the Henry III of Castile to the court of Timur, recorded his experiences of Samarkand in glowing terms:

As mentioned to this festival we had been invited. Both the garden and palace here were very fine, and Timur appeared to be in excellent humour, drinking much wine and making all those of his guests present do the same. There was further an abundance of meat to eat, both of horse-flesh and of mutton as is ever their custom. When the feasting was over his Highness gave command that each of us ambassadors should be presented with a robe of kincob [gold brocade] and we then were allowed to retire going back to our lodging which was situated not far from this palace where Timur had been feasting. At all these banquets the crowd of guests was so great that, as we arrived and would have approached the place where his Highness was seated, it was always quite impossible to make our way forward unless the guards who had been sent to fetch us would force a passage for us to pass. Further the dust around and about was blown up so thick that our faces and clothing became all of one colour and covered by it. These various orchards and palaces above mentioned belonging to his Highness stand close up to the city of Samarqand, while stretching beyond lies the great plain with open fields through which the river [Zarafshan] flows, being diverted into many water-courses.

~ Embassy to Tamerlane, 1403-1406 (2009) by Ruy González de Clavijo, translated by Guy Le Strange

—-

All architecture of Samarkand – whether mosque, madrasah or mausoleum – is distinctive for its blue-green colour. In a 1992 essay called “The Heavenly City of Samarkand” published in the magazine The Wilson Quarterly, the historian of Islamic art and architecture Roya Marefat outlined a number of reasons behind the use of the shades. According to her, “Because blue was the color of mourning in Central Asia, it was the logical choice for most funerary architecture. But the preference reflected a range of other, more favorable symbolic associations. As well as being the color that wards off the evil eye (a function that it still performs on the doors of many Central Asian houses), blue is the color of the sky and of water, the latter being a precariously rare resource in Central Asia and the Middle East. Abetting this clearly overdetermined fondness for the color is the fact that the region abounds in such minerals as lapis and turquoise.”

Scroll down for illuminations, paintings and photographs related to the city.

See more pictures here and here.

—-

Further Reading:

Lost Enlightenment: Central Asia’s Golden Age from the Arab Conquest to Tamerlane (2013) by S. Frederick Starr

Central Asia in World History (2011) by Peter B. Golden

The Silk Road: A Very Short Introduction (2013) by James A. Millward

Lonely Planet Central Asia (2014) by Bradley Mayhew, etc.

Uzbekistan (Bradt Travel Guide) (2013) by Max Lovell-Hoare and Sophie Lovell-Hoare

Uzbekistan (Cultures of the World) (2005) by Mary Lee Knowlton

Tamerlane: Sword of Islam, Conqueror of the World (2007) by Justin Marozzi

—-

Image Credit:

Featured: Bibi-Khanym Mosque, Pixabay

—-

![]()

Such incredible architecture and artwork! xx

LikeLiked by 1 person

Totally! I love the paintings too.

LikeLike

Stunning pieces of architecture! It was interesting to learn about what the colour blue symbolises as well..Great read!

Divya

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! Yes, I particularly liked that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Beautiful

LikeLiked by 1 person

What amazing artwork ! So beautiful !

LikeLiked by 1 person

yes beautiful

LikeLiked by 1 person