I have always been too conscious of our dependence on time. I remember almost all of the major clocks and watches I’ve encountered in my life – at home, in school, in college, in every temporary room in the few countries in which I have lived. Until last year, time, for me, was a strange phenomenon, simultaneously linear and cyclical, that impressed a sense of order upon existence. All was contingent upon it but mostly, it seemed like a generous unfolding. A blessed gift. A mysterious aspect of reality that graciously accommodated and contained everyone and everything.

It is only now, in the capacity of an emerging independent blogger, that I have had the chance to confront time’s other, darker facet – its sheer tyranny and incorrigibility. I panic and hyperventilate on a daily basis. How much do I read? How much do I write? What about emails and networking on social media? Also, I may write about other artists and thinkers but would I ever be able to produce something of my own? The time behind my calendars and to-do lists is impervious to pleas. Nauseatingly dominating. I adhere to my plans for three days, then I wake up late on two days and I am a total waste. Time is never amused.

As I dueled away – am dueling away – with the tireless invisible and intangible system that separates events into past, present and future, I thought I might like to check out Timekeepers: How the World Became Obsessed with Time (2016, Canongate) by British journalist and author of several non-fiction books Simon Garfield (@simongarfield), who, according to the Guardian, is “the thinking grown-up’s favourite teacher.”

Timekeepers is not a book on the physics of the nature of time or the fictions of time travel (what came before the Big Bang, etc.; going back to kill your grandfather, etc.). Instead, it is a playfully philosophical cultural history. Garfield considers, how, over the past 250 years, time has become such an insistent force in our lives. Time, once passive, is now aggressive. “After tens of thousands of years of looking up at the sky for vague and moody guidance,” the author tells us, “we now take atomically precise cues from our phones and computers not once or twice a day but continually and compulsively.” With the help of illuminating stories, he shows us how we managed to bring this cauldron of rush upon ourselves and asks whether we have all gone completely nuts. He doesn’t scold us for our fast living but does come up with suggestions on how to apply the brakes.

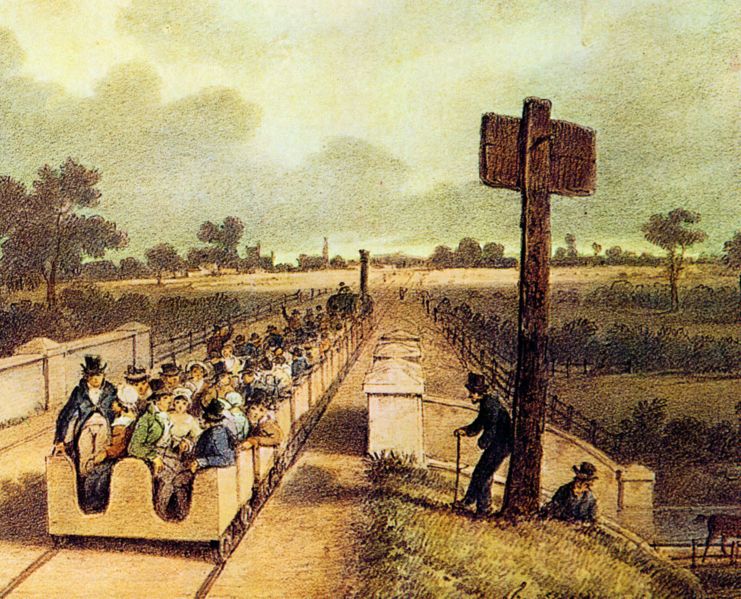

Many of us have heard of sophisticated old calendrical systems – from Mayan to Gregorian – that drew upon the astronomical occurrences of solstice, equinox and eclipse and inscribed political and religious codes upon the passage of seasons. But even within these complicated devices of measurement, time seemed fairly wide and large. Our current obsession with short deadlines and preoccupation with tiny cogs and springs and flywheels have a lot to do with the idea of the train. Garfield writes:

The steam engine both shrunk and expanded the world; it enhanced trade; it hastened the spread of ideas; it fired global industry. And more than any other invention – save the clock itself and possibly the space rocket – the railways changed our appreciation of time.

They also gave rise to nationwide standardisations.

Garfield discusses how our modern conception of time has been manipulated or depicted or experimented with in politics, athletics, music, film, photography, urban planning – while inserting tips on time management and intriguing information on the mechanics and business of horology (within which I found the bit about the luxury Swiss watch manufacturer Patek Philippe & Co., founded in 1851, particularly interesting).

An excerpt from the Ninth:

the world waking up to that photo hung in suspended time. Everyone drew breath…This was unforgivable inhumanity. The war had to stop. A single image taken in a fraction of second (and it is always the personalised image of a few that amplifies the suffering of millions), brought the story home. It helped, as it always does, that the victims were children, innocent and bewildered.

When it comes to film and time, one cannot miss the American comedian and filmmaker Harold Lloyd’s (1893-1971) Safety Last! (1923), in which, holding the hands of a large clock, he hangs by a skyscraper over moving traffic. This enduring moment is the most desperate image in all of silent cinema – “a vision of Everyman,” Garfield comments, “successfully hanging on as time falls away.”

Watch the trailer:

In photography – certainly, the Napalm Girl from Vietnam! On the morning of June 8, 1972, the 21-year-old Vietnamese photographer Huỳnh Công Út (aka Nick Ut) set off for Trang Bang, a small village north-west of Saigon. Just after noon, he saw two planes dropping bombs and people running in distress, fleeing towards him. Within a group of five children, he saw a nine-year-old girl with burns on her skin. She had shed her clothes and kept screaming “nóng quá” (too hot!) with her arms outstretched. Nick Ut then took the picture that would win him a Pulitzer and much fame. The world saw “The Terror of War”. “For a short while,” Simon Garfield writes:

A short video from the Associated Press featuring an older Napalm Girl – Phan Thị Kim Phúc (born 1963), now a Canadian citizen:

The only part of Timekeepers that I did not find too engaging was the penultimate chapter – which is, among other things, on Prince Charles’ Poundbury Estate located on the outskirts of Dorchester in Dorset, where he has planned a community that combines “beautiful dwellings with nearby workplaces and shops”, where “traditional values are upheld” and “kids play hopscotch in the spotless streets.” A powerful man, Garfield points out, “does have that rare and enviable ability to turn back time.”

But the closing section “The British Museum and the Story of Us” was too thrilling. Here is an institution that, according to the author, “marks the passage of time like no other”. Opened in January 1759, the museum is driven by a desire to “order and explain events beyond randomness”. It is a living symbol and demonstration of time: “time passing, time tracked, time catalogued.” As it protects and promotes old and heavy objects on pedestals, behind glass, it shows how cultures varied and grew. It captures the movement of time in concrete form. In doing so, the museum tells our tales. Stories, maintains the author, are, in the end, the best way of making sense of time. As our planet, the cosmically insignificant “pale blue dot” (reference Carl Sagan) spins away, the narratives we share of ourselves with each other help us accept the flow of time. They also provide a diversion from the harsh reality of the end of time – our mortality.

Well-researched and superbly written. A fun read with a heartening conclusion.

—-

Image Credit:

Featured: Pocket watch by User “timlewisnm”, CC BY-SA 2.0, Flickr

—-

![]()

Just recently because of my mental disorder, I have always been a stickler and slave to time. Uncle Denis.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Do you know about this clock in Bristol? It has Bristol time too from before the railway adjustment. https://c1.staticflickr.com/3/2152/2080844004_8431c9caf4_z.jpg

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for that! The writer does mention how several city officials objected to the interference from London – and clocks with two minute hands (local+national) were used to display their disapproval.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yep this is the case with the Bristol one – that is not a second hand

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am interested in timekeeping – some of my ancestors made watches

LikeLiked by 1 person

That is awesome. I’ll be reading more on horology now.

LikeLiked by 1 person

They had branches in London and Horsham, Sussex. It has always been a family thing that we are descended from the great marine chronometer man, John ‘Longitude’ Harrison – but although my family research ended up in the same village have never been able to prove that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This guy – wow! https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Harrison

LikeLike

It will be that guy – initially he worked mainly in wood.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sounds fascinating. I recently read Deep Survival by Laurence Gonzales. Some authors can make any subject engaging.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just checked it out – sounds interesting. Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating post. Thank you.

The mention of the silent film Safety Last! here brings to my mind another silent film of the 1920s: Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. In one particularly memorable scene, the hero takes the place of a laborer with a machine that looks like a large clock. The hero quickly becomes exhausted trying to operate it, and in his feverish state, the machine DOES transform into a clock which he struggles against desperately trying to make time pass more quickly — and, not coincidentally, he begins to resemble Christ on the cross.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Joshua, thanks for following my blogs. Metropolis is an all time favourite of mine! I mentioned it recently in a post on the dystopic depictions of the modern city: https://onartandaesthetics.com/2016/11/03/noir-urbanisms/

In this scene, indeed, Freder Fredersen looks like Christ carrying the cross.

LikeLiked by 1 person