On September 13, 2016, I published a post on a very intelligent book on urban loneliness called The Lonely City: Adventures in the Art of Being Alone by British writer and critic Olivia Laing. The modern city – a set of cells, a concentration of glass and concrete and gneiss – is designed in such a way that it simultaneously exposes and entraps people. It is here that loneliness reaches its apotheosis – in a crowd. A few days ago, I stumbled upon a whole collection of academic essays called Noir Urbanisms: Dystopic Images of the Modern City that examines not only the alienation but also the crisis and catastrophe engendered by the contemporary metropolis. In art – across film and painting and literature – urban landscape is frequently portrayed with a dystopic flavour, as a terrifying world of darkness in which the elite few erect sturdy and shimmering structures by manipulating and exploiting the vast many. Noir Urbanisms traces these dystopic depictions of the modern city through Germany, Mexico, Japan, India, South Africa, China, and the United States. Topics include:

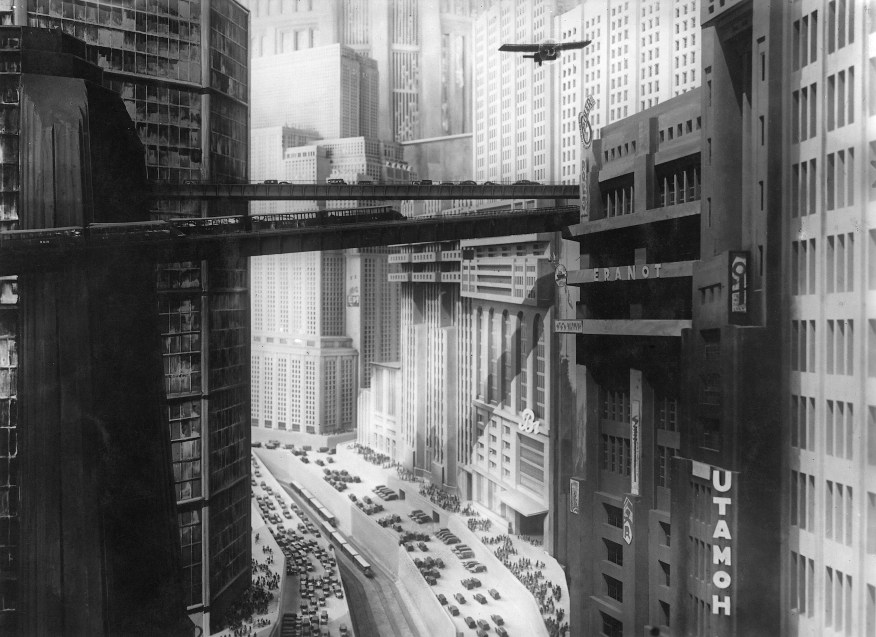

Weimar representations of urban dystopia in Fritz Lang’s 1927 film Metropolis; 1960s modernist architecture in Mexico City; Hollywood film noir of the 1940s and 1950s; the recurring fictional destruction of Tokyo in postwar Japan’s sci-fi doom culture; the urban fringe in Bombay cinema; fictional explorations of urban dystopia in postapartheid Johannesburg; and Delhi’s out-of-control and media-saturated urbanism in the 1980s and 1990s.

The editor of the volume, Gyan Prakash, professor at Princeton University, explains the link between the broad philosophical/artistic movement we call “modernism” and the rapid urbanisation of the twentieth century, shedding light on the origins of the dystopic descriptions of the city. He writes:

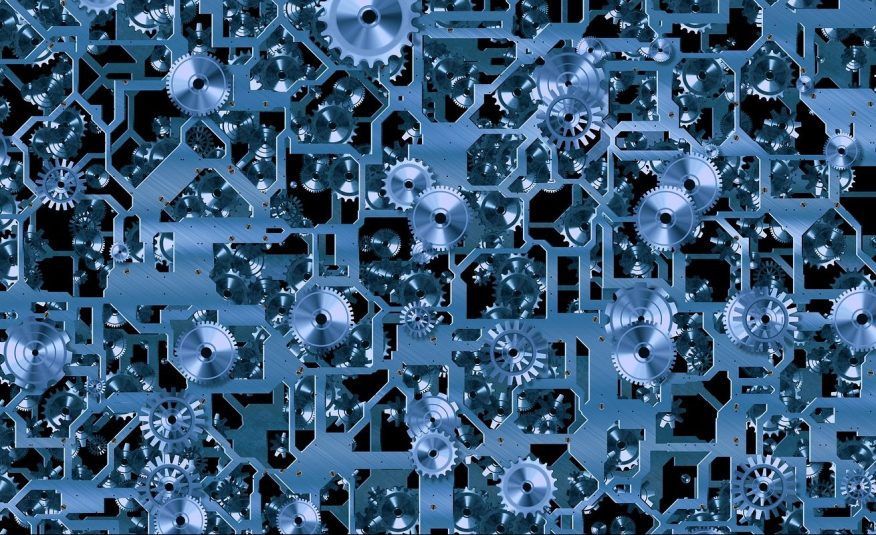

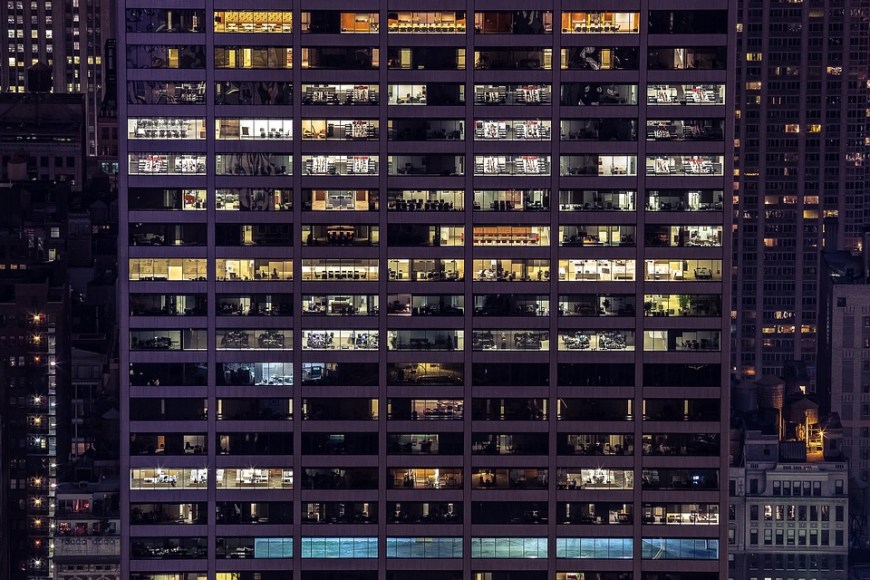

Modernism was a uniquely metropolitan phenomenon. Emerging from the tumultuous changes of the twentieth century, modernism represented the high-culture expressions of the city. As writers, poets, artists, architects, and filmmakers breathed the air of rapidly changing and growing cities, they were exhilarated by the new urban experience. For poets and novelists, the street appeared as the magical stage for the enactment of modern life. The found the chaotic energy of the traffic and the maelstrom of the crowd awe-inspiring. Writers and filmmakers alike were fascinated by the clockwork-like rhythm of daily life as thousands of workers and office-goers entered and exited their workspaces at regular hours. As technology reshaped the cityscape, the spirit of architects and designers soared. Harnessing the awesome power of science and technology, they planned utopias of perfectly designed and synchronized housing, streets, traffic, and artifacts of daily life.

But a shadow always hung over the modernist halo. Inequity and oppression punctuated the drama of freedom on the street. The experience of immersion in the crowd produced feelings of estrangement and atomization, and the gathering of the multitude could easily become part of the spectacle of mass society that capitalism staged. The rhythm of daily urban life might suggest a symphony, but it also spelled the boredom of routinization. The awesome promise of technology and planned futures was also terrifying. One way in which modernism expressed this terror was through the image of urban dystopia. Its dark visions of mass society, forged by capitalism and technology, however, did not necessarily mean a forthright rejection of the modern metropolis but a critique of the betrayal of its utopian promise. The dystopic form functioned as a critical discourse that embraced urban modernity rather than reject it.

A definitive image of urban dystopia is the German science-fiction film Metropolis (1927) in which wealthy capitalists rule from high-rise buildings while workers are abused underground. “Embodying the power of technology that it critiques,” writes the editor, “Metropolis is caught between being enthralled and frightened by the machinic big city.”

Later, in 1940s and 1950s Hollywood, the genre of “film noir” projected a mood of urban anxiety and nihilism. Lighting was used not only to define space but also to inflect it with psychological character and motivation. Film noir, Prakash adds, “represented the city with images of deserted streets, crumbling neighborhoods, shadowy spaces and glittering skylines, petty criminals, elliptically speaking hard-boiled detectives, and characters with ambiguous and sexual motivations.”

As long as our technologists continue to engineer ever-greater utopias, I believe, our artists will keep conjuring sleeker and smarter expressions of dystopia.

—-

Image Credit:

Featured: Pixabay

—-

![]()

Chaplin’s Modern Times is a wonderful example of an artist trying to bring humor and humanity to a crushing darkness. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IjarLbD9r30

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks! What an epic film!

I’m also very interested in neo-noir…

LikeLiked by 2 people

Despite my mental ailments, I love and praise all your blogs.

LikeLiked by 1 person

In pursuit of technical intelligence and expertise, love and simplicity has been sacrificed. Such that everything created no longer carries the passion for survival, but the arrogance of prestige.

LikeLiked by 3 people

You’ve put it very well! Thanks for commenting. 🙂

LikeLike

Thanks for referring me to this post, Tulika. Metropolis has so many fascinating aspects to it, including the Christ imagery in that unforgettable clock/machine scene. I would love to see the original cut (four? six? hours long!), but I believe it went missing decades ago.

As far as other films deserving mention here:

Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1981) – the director’s cut works better (the studio insisted on the voice overs, which had the unfortunate effect of lessening the alienating impact of the visuals).

Terry Gilliam’s Orwellian satire Brazil (1985)

George Lucas’ first film, THX1138 (1971) – sadly underrated, one of the best modern dystopian films. It has a dark humor to it usually overlooked.

St. Petersburg seems to have a life of its own in Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment — not a dystopian novel per se, but certainly the portrayal of the city has dystopian undertones.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You might find this book interesting…”The Philosophy of Science Fiction Film” – It has a great essay that links Metropolis to the “Dialectic of Enlightenment” (1944) by Horkheimer and Adorno.

Blade Runner, of course, is awesome. I read how the personality of Rachael borrowed from that of the Maschinenmensch.

I have heard of both Brazil and THX1138 – have to watch them! Thanks for suggesting.

I love Crime and Punishment but have always concentrated on its monologues, conversations and philosophy – the mental stuff. Never quite paid attention to the character of the physical city. I will check that out sometime.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, and your post brings Margaret Atwood poem to mind as well:

THE CITY PLANNERS

Cruising these residential Sunday

streets in dry August sunlight:

what offends us is

the sanities:

the houses in pedantic rows, the planted

sanitary trees, assert

levelness of surface like a rebuke

to the dent in our car door.

No shouting here, or

shatter of glass; nothing more abrupt

than the rational whine of a power mower

cutting a straight swath in the discouraged grass.

But though the driveways neatly

sidestep hysteria

by being even, the roofs all display

the same slant of avoidance to the hot sky,

certain things:

the smell of spilled oil a faint

sickness lingering in the garages,

a splash of paint on brick surprising as a bruise,

a plastic hose poised in a vicious

coil; even the too-fixed stare of the wide windows

give momentary access to

the landscape behind or under

the future cracks in the plaster

when the houses, capsized, will slide

obliquely into the clay seas, gradual as glaciers

that right now nobody notices.

That is where the City Planners

with the insane faces of political conspirators

are scattered over unsurveyed

territories, concealed from each other,

each in his own private blizzard;

guessing directions, they sketch

transitory lines rigid as wooden borders

on a wall in the white vanishing air

tracing the panic of suburb

order in a bland madness of snows

~ Margaret Atwood

LikeLiked by 1 person

Complex and very interesting! I love the image of those sliding houses…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on VIRTUAL BORSCHT .

LikeLike